The Brookline Bird Club: 1945-1988

In 1945 Douglas Sands, “just out of the Army,” entertained Brookline Bird Club members with a slide show on the “Fauna and Flora of the Galapagos Islands.” Two years later, “moving pictures” illustrated lectures on rare American birds and an Alaskan mountain climb. The club’s 1945 statistical report listed Common Eider, Harlequin Duck, Purple Sandpiper, and Northern Mockingbird among the highlights. The traditional boat trip to Provincetown-with binoculars again allowed-resumed in 1946. Wartime was over.

The first two decades after the war were a plateau period for the BBC. Membership dipped from 386 in 1943 to 325 in 1947, leveled off and slowly climbed to 465 in 1963 (including 30 from 9 states beyond Massachusetts)-still below the 558 in 1928. Club trips dropped to a low of 97 in 1961. In 1960-a “year of turmoil” according to the statistical report- one bulletin listed several trips with “leader to be chosen from among those present” and declared that the club could no longer provide reliable train and bus directions “because of drastic curtailment of public transportation and frequent changes in timetables.” In 1945 the BBC had relied on public transportation for almost all trips, but by 1960 auto trips were heading for Essex County, the South Shore, Westport, and Mt. Greylock. On a split-group outing in 1952, one party strolled the length of Plum Island, while the other toured the refuge by car. The BBC also offered regular “supper walks,” excursions to Martha’s Vineyard, and several 10-day trips to Bull’s Island in South Carolina.

Ludlow Griscom 1959

Ludlow Griscom. Photo presumably taken by BBC member Leon Keach in 1959, a few months before Ludlow's passing. Kindly donated by Phil Lussier.

Though trips declined, the BBC species total per year gradually rose to a high of 275 in 1962. Newburyport, including the Parker River refuge, was the most consistently productive birding area. Trip leaders often used the Argue Field Cards, designed by eventual club president Arthur Argue. The club bought a spotting scope, which moved about from leader to leader. With the impetus of Roger Tory Peterson’s classic field guide and the rigorous example set by Ludlow Griscom, members became more adept at field identification. Rarities found on club trips included a Chuck-will’s-Widow at Mt. Auburn in 1952, a Black-headed Grosbeak in Beverly in 1958, a Tufted Duck in Newburyport in 1959, a Brown Booby in Newburyport in 1961, a Black- throated Gray Warbler at a Winchester feeder in 1962, and in 1963-the first of several years of “severe drought”-a Green-tailed Towhee in Magnolia.

More striking were the misses and write-in status of birds now far more common in Massachusetts. In 1988 Larry Jodrey recalled: “We had to go a long ways to find a Cardinal or Mockingbird. . . House Finches! Nobody ever heard of a House Finch.” A BBC legend has it that Henry Wiggins “blew” a House Finch across the Rhode Island line to add it to his state list.

House Finch and Tufted Titmouse were still write-ins on the Mass Audubon checklist as late as 1972, though by 1963 flocks of both species had become regular. Write-ins on BBC year lists included a Red-bellied Woodpecker in Rockport in 1953, nesting Carolina Wrens in Orleans in 1959, and a dozen+ Harlequin Ducks in Magnolia in 1963. Missing from some lists were Mute Swan, Snow Goose, Gadwall, Great Egret, Snowy Egret, Willet, Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, all three jaegers, Eastern Screech Owl, Whip-poor-will, Winter Wren, and Orchard Oriole (three straight years). The BBC seldom saw more than four owl species a year. Great Horned was missed as recently as 1969.

In the 1950s the BBC mourned the passing of some longtime leaders. Grace Snow, longtime statistician and recording secretary, died at age 75 in 1950. She had kept birding until the end of her life “despite handicaps which would have confined an ordinary person to a rocking-chair existence.” Ethelind Merritt, former vice-president and one of the first directors, died while mailing club correspondence. Former president Leslie Little, known for his skill and patience in the field, had “looked up the club” as soon as he got out of the Army at the end of World War I. A 1958 memorial honored L. Raymond Talbot, certainly one of the most impressive leaders in club history: a former professor of Romance Languages at Boston University, club president for 16 years altogether, tireless mentor of young birders, and a director almost to his death at age 67. Known for his toughness in “the days of hardier birding in the 1920s,” Talbot had travelled much of the world, sending home letters about Saharan sand storms and Wallcreepers in the Pyrenees. He was, the memorial stated, “outspoken in support of his moral convictions” and “felt with uncommon sensitivity the beauty of color and sound, of landscape and living things.”

Poetry, absent from blue books (if not the hearts of birders) since the 1930s, returned in the 1960s in bulletins and statistical reports painstakingly compiled by Dorothy Caldwell and then-for 23 years–Mary Lou Barnett. Alighting in blue books were Robert Frost’s winter owl displaying “underdown and quill to glassed-in children at the window sill,” Dorothy Cairn’s Snowy Owl in “far, snow-muted space,” and Herb Kenny’s starling: “Be warned, people. I am spangled death. I am the adaptable.” Jerry Soucy’s “Good Harbor Beach-Portrait in Grey” evoked a day alone on the Gloucester beach when seabirds flocked and dunes were “driven high by cruel November seas.” One bulletin quoted the late Edward Howe Forbush, who believed that the greatest “boon” of birds is to keep the human spirit young: “Their songs are voices from our vanished youth.” Sometimes the poetic spirit broke out into playfulness. In 1962 John Day put forth the nominating committee slate in rhymed stanzas, while wishing for “longspurs land-lappy and rails, kingly and clappy” in the coming year. Arthur and Margaret Argue issued a lighthearted bird identification quiz, following this format:

| What Bird? | Clue | Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Roving Stool Pigeon | Shorebird (W. Coast) | |

| Donkey Game | Duck | |

| Psychoanalyst | A Rocky Mt. Bird |

Readers can fill in the answers.

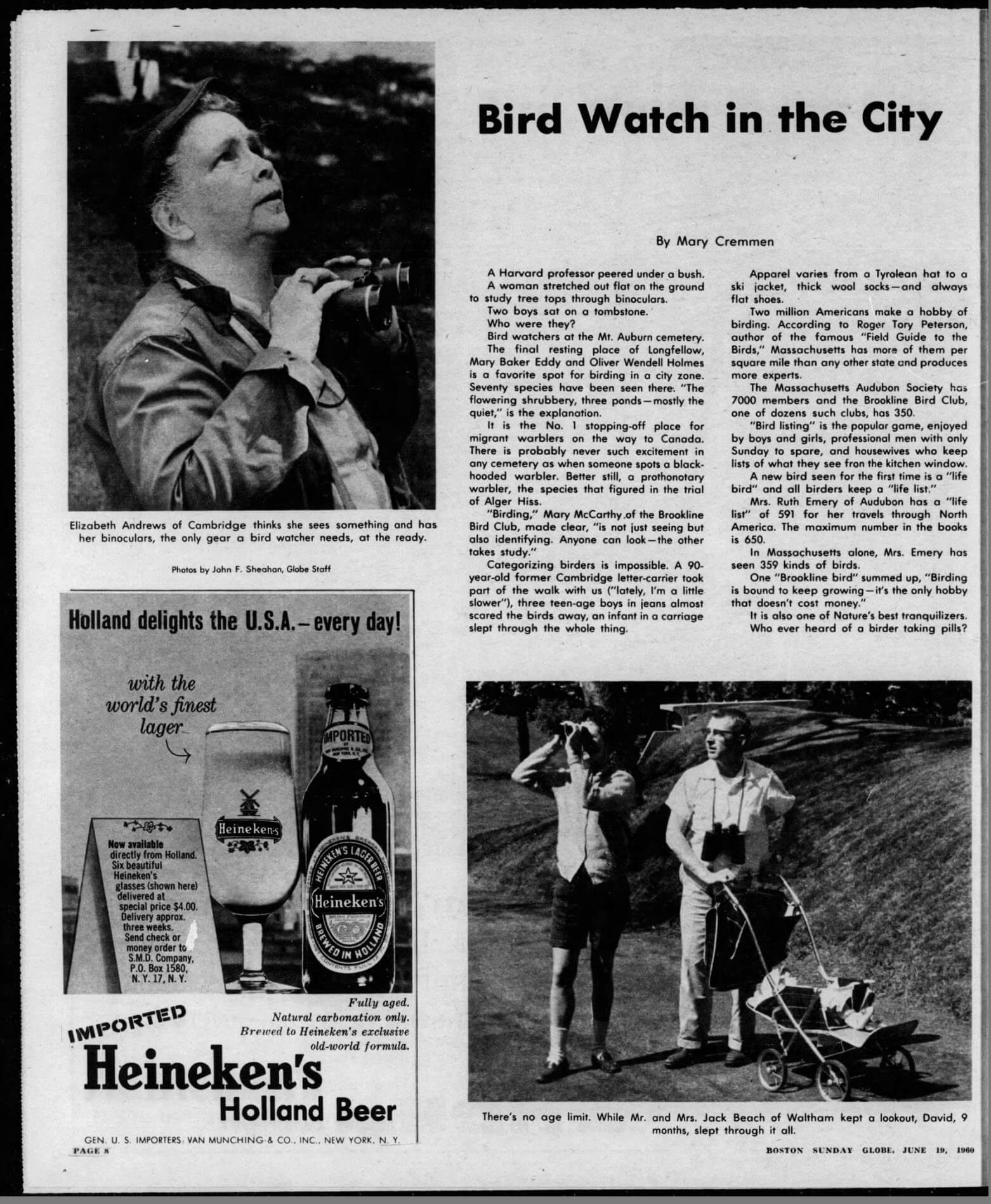

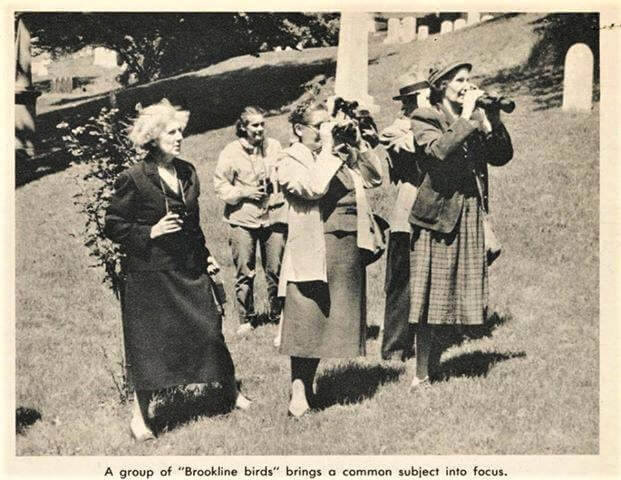

Brookline Bird Club at Mount Auburn in 1960

Historical view of birders at Mt Auburn Cemetery from Boston Globe Magazine

In 1963 a well-attended 50th anniversary gala at the Museum of Science featured a talk by club member John Kieran-once described by The Boston Globe as “the most widely-known birder in the nation” and surely the only inductee in the Baseball Hall of Fame (as a sportswriter) with a bird sanctuary (in Rockport) named after him. Larry Jodrey reflected on BBC history: “Few bird clubs in the nation can boast of such a continuous and full program of field trips.” Since its inception the BBC had sponsored 5243 trips and seen all 282 species on the Mass Audubon checklist, 57 write-ins and more birds out of state. Jodrey thanked the club for affording him the chance to see and study birds with “agreeable companions.” In the spirit of Wilson and Audubon, he encouraged members to keep working for the recognition of birds as an “important part of our national heritage” and the protection of birds for their own sake and for future human generations.

The years after 1963 witnessed a steady surge in BBC membership and activity. In 1967 Time published a piece on birding, generously estimating that 11,200,000 Americans were now bird watchers. Apparently, birding was becoming more fashionable, though, as Jodrey later recalled, witty civilians would still roll down their car windows to holler “tweet, tweet, quack, quack” at roadside birders. Club membership nearly tripled from 548 in 1966 to over 1600 in late 1977, then fluctuated around 1400 to 1500. The club offered what The Boston Globe called “a feverish field trip schedule,” sponsoring 219 trips with 301 species seen in 1972. By 1977, directors were asking, “How many is too many? Is BBC growth to be unlimited?” They rejected the idea of hiring employees to help manage club business. Ironically, in 1977 when the BBC was at its largest and most active, the justifiable phrase “America’s Most Active Bird Club” was changed to “founded in Brookline in 1913” on each blue book’s back cover. That year a life membership increased to $50. In 1982, operating in the red and relying heavily on contributions, the BBC finally raised annual dues to $3. “We need leaders,” sometimes in bold, became a standard bulletin reminder. In 1981 the odd phrase “word processor” crept into club minutes. In 1987 the club put its files on a computer.

From 1963 to 1975 the BBC expanded its range to include regular trips to Nantucket and the Boston Harbor islands, camping on Cape Cod and in the Berkshires, out-of state trips to the Isles of Shoals and the Maryland shores, and hawkwatching on Mt. Tom and Hawk Mountain. A 1970 group “birded,” studied skins, and wryly added extinct species to the BBC life list at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Across town, walks at Mt. Auburn Cemetery became a club institution, with its own lore and lingo. On Jodrey’s first outing there, he was thrilled by the birds and the ambience, but puzzled when the leader called out, “There’s an Indigo Bunting over by Eddy’s place”-presumably a neighborhood bar, not a monument to Mary Baker Eddy. On one walk led by Bob Stymeist, a new bride and novice member asked, “What is that worm eating?” In a 1970 bulletin piece Stymeist described “Sweet Auburn” as “probably the best place in Eastern Massachusetts to observe the migration of land birds.” As evidence he cited the 81 species, including a Cerulean Warbler, seen in four hours on a BBC walk that May. When Stymeist went into the service in 1968, the BBC pleaded for leaders to replace him. When he returned in 1970, he led Mt. Auburn walks almost daily that spring. Boston Globe articles on “bird chasers and meadow haunters” in 1975 and 1986 noted his “regular surveillance” of the cemetery-along with “Caution: Birdwatchers” bumper stickers and a PETREL license plate- and called Mt. Auburn “one of the most persistently birded areas in the country,” with BBC walks sometimes drawing an “unwieldy 100 or more” participants.

Club highlights during this period included a “thoroughly scrutinized” presumed-escapee American Flamingo at Plum Island in 1964; Peregrine Falcons at the Parker River refuge after towers were erected in 1965; six Henslow’s Sparrows (“slowly dying out” in the state) at Plum Island and a “strange shorebird” that led to “unanimous indecision” in 1967; a Saw-whet Owl found by a Gloucester librarian and two teenage girls on their first bird walk in 1970; a BBC life- bird Common Raven at the Quabbin and the first known nesting Barn Owls on Nantucket (found by Edith Andrews) in 1971; a Painted Bunting in Barre on New Year’s Day in 1972; a two-day- wonder Sharp-tailed Sandpiper in Newburyport in 1973; a Sabine’s Gull tracked down by a coordinated BBC strategy on Nantucket in 1974; Western Meadowlarks three different years; and an “old friend” Eared Grebe at Bass Rocks in Gloucester for eight straight seasons.

Some years were especially memorable for the abundance and variety of birds: 1969, “the best season that our club has observed,” when the BBC life list reached 351, and 1974, with “the best migration in 25 years.” Other years were relative busts: 1967, “the year without a spring;” 1972, the year of “endless deluge;” and 1978, with extremes of cold and heat, drought, dismal migrations, the “worst year ever” for many club members. Birds missed by the BBC in one or more years included Harlequin Duck, Little Blue Heron, Glossy Ibis, Cooper’s and Sharp- shinned Hawks, Bald Eagle, Pileated Woodpecker, Carolina Wren, and Blue-gray Gnatcatcher.

Meanwhile, more members were drawn to the lures of the list and the chase. In the early 1970s the BBC instituted an annual Century Run, or Big Day, typically traveling from Great Meadows to Plum Island and “NOT recommended for beginners.” The 1974 Run found 162 species, including a nesting Henslow’s Sparrow that vocalized at 3:15 a.m. in Newburyport. The next weekend, the team of Bob Stymeist, Terry Leverich, and Tad Lawrence set a state Big Day record of 173. The Boston Globe chronicled the 1975 BBC Run. Eleven “quick-eared and sharp- eyed” birders began at 1:00 a.m. with a missed Chuck-will’s-widow reported near Harvard Divinity School, and found their last species (#159) at dusk with high beams at Newburyport Harbor. In 1971 Jerry Soucy began listing individual checklist totals in his annual Year in Review. Eight BBC members saw 300 or more species that year. Trip leader David Brown often topped the list, reaching a record high of 336 in 1983. Soucy’s reviews, which went beyond the BBC to cover all birding in Massachusetts, combined species highlights and misses with wisdom about birding. He defended listers on the grounds that they usually compete only with themselves while maintaining reliable, important records of sightings.

The club’s outings were recorded in vivid detail by Mary Lou Barnett, quoting field card comments that were often “witty, poetic, and occasionally philosophical,” though she had to admonish some leaders-like one who reported 125 Loggerhead Shrikes-to proofread their cards. Barnett sometimes provided the poetry herself, describing birds in May “mad with glee,” and “Whip-poor-will walkers” accompanied by “the winking enchantment of fireflies.”

One recurring image in her reports is that of “indefatigable” and “doughty” birders up again the elements: gale-blown at Crane Beach, frostbitten at Mt. Auburn, in “snow up to the knee” at Plum Island, and, in Marblehead, finding fog, heavy surf, and surfers-but no birds. In 1966, an eager “sheriff’s posse” of over 40 braved ice, soaking mist, and blinding sleet, “beat the bushes and crawled in the snow” to find “sweet victory”-a Rock Wren in Rockport. In 1969, another sizable group, frozen but “lighthearted with exuberance,” found 13 turkeys (a life bird for 13 participants) at the Quabbin on the BBC’s first Wild Turkey Hunt. Some days brought more exuberance than others. One frigid March morning in 1972, Larry Jodrey expressed a feeling known to all leaders of winter Cape Ann trips-the hope that no one will show up.

Another trip leader proposed that the BBC “ban winter birding.” Paul Roberts recalls one pelagic trip when, in “cold, rough seas,” the boat lost power and pitched and rolled out of control. “Atlantic Puffins could have been standing on deck and passed unnoticed.” Jerry Soucy eventually swore off pelagic trips altogether: “I have spent too many tortuous hours on rocking boats and so I depend on coastal storms to bring pelagics to me.”

Other challenges came from gas shortages, Plum Island hunters, and fellow birders, like the one who tested the leader’s aural skills by joining the Plum Island auto caravan on his motorcycle, or another known as “Mrs. Nudge-in” because she always got right behind the leader’s car on any caravan she joined. On one trip, a Boxford farmer sent his daughter out with a broom to scare off the Western Meadowlark luring birders to the edge of his property. Equally territorial was the Nantucket man who came out with a gun in one hand, a glass of whiskey in the other, as birders studied a Jackdaw that wasn’t even on his land. Some members were undaunted by any obstacle. In 1969, after a lone trip leader trudged six miles in zero degree weather (and found 18 species) on New Year’s Day at Crane Beach, Barnett reported: “Mr. Jameson said he enjoyed his walk.” In 1978 Herman Weissberg found an Acadian Flycatcher singing at Pike’s Bridge Road the day before he entered a hospital for open-heart surgery.

Birds, beasts, birders, and civilians all conspired to add comedy to Barnett’s reports. In 1970, an overexcited member, trying to help his comrades see a Cattle Egret in Rowley, set up the group’s only scope in a manure pile. In 1971, the sighting of five Northern Fulmars on a pelagic trip led to a “mad scramble” and postcoital birders jitterbugging on deck. In 1974, club president Eliot Taylor whistled at dusk for a Whip-poor-will in Sherborn. A donkey responded. And in 1975, on a Greylock campout led by Steve Grinley, a member was asked to move his car so someone could jump off the mountain. The member obliged. Six hang gliders appeared and jumped. The last one flailed into a bush but took flight with the assistance of birders, who carried on to find the Mourning Warbler they were after.

1975 was also the year of “the find of the century,” a Ross’s Gull, first glimpsed in January at Newburyport Harbor by BBC directors Phil Parsons and Herman Weissberg, then, almost two months later, re-found and verified in Salisbury by Walter and George Ellison. A first record for the Lower 48, the Ross’s made the front page of The New York Times and was seen by thousands of birders and curiosity-seekers from across the country-over 500 observers on one day in March.

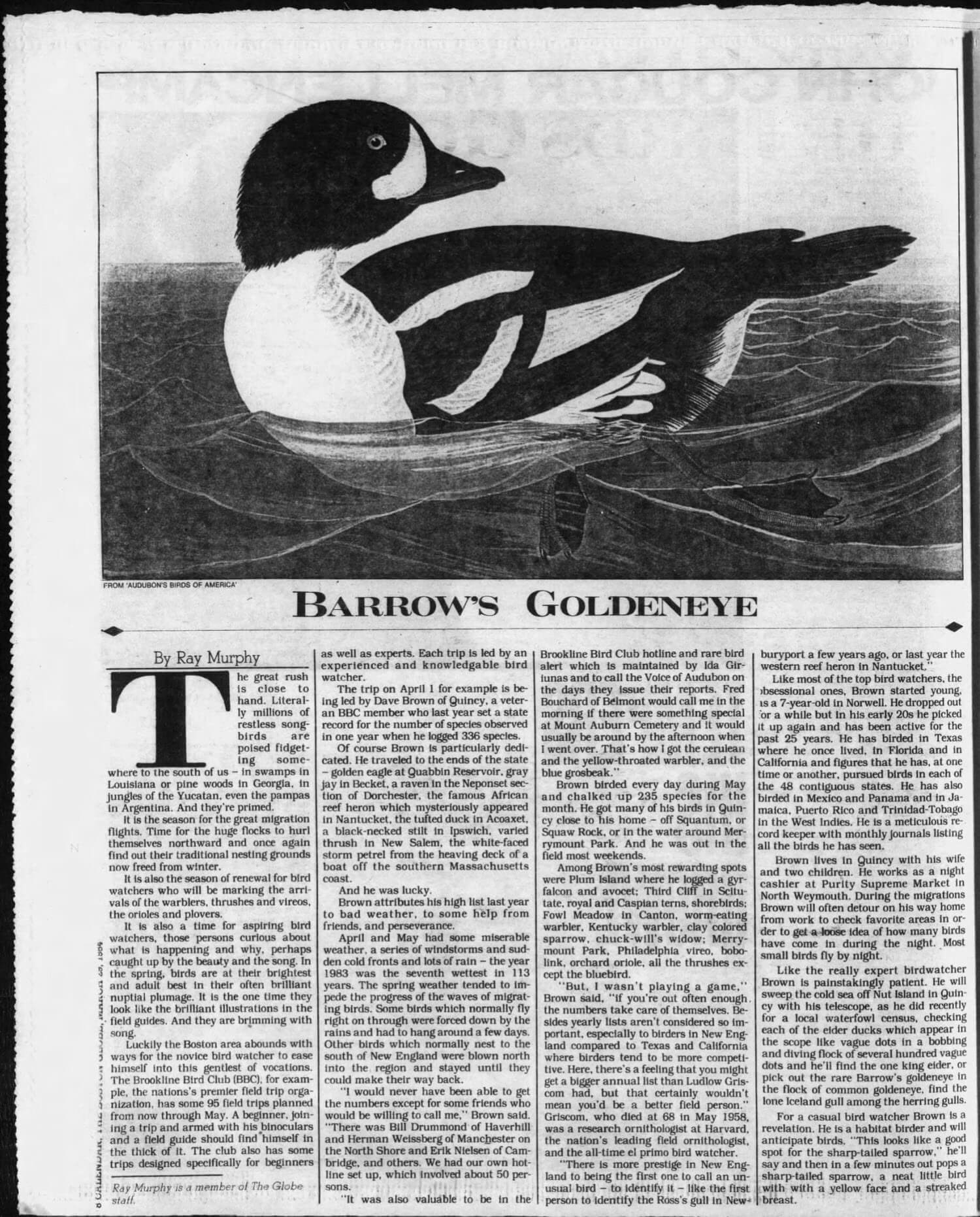

Some wondered if the bird was a harbinger, or a BBC recruiting agent, for the Ross’s was followed by a spectacular string of rarities: a Northern Wheatear discovered that fall when Dick Hale took a wrong turn on a BBC Nantucket trip; a Black-browed Albatross seen by four club members as it swooped close to their fishing boat out of Rockport; an Ivory Gull in Salisbury in December 1975 watched by a thousand birders the first weekend (and “was fed bologna sandwiches but did not beg”); Black-backed, Red-headed, and Red-bellied Woodpeckers on the same day in Gloucester in December 1976; a “once in a lifetime” Steller’s Eider in Scituate in March 1977; a northeast-record McCown’s Longspur in Bridgewater that same year; a Boreal Owl in Salisbury on the last day of 1978; a Great Gray Owl in Rowley, 79 Sooty Terns after Hurricane David, and a Lucy’s Warbler in Ipswich in 1979; Eurasian Cuckoo, Redwing, and Spotted Redshank (all state records) in 1981; Brown-chested Martin on Monomoy and Jackdaw on Nantucket (both state records) in 1982, as well as an “unrecognizable dead bird” that was carried home by a cat, taken to Manomet, and determined to be a Marbled Murrelet (a first East Coast record); a Western Reef Heron on Nantucket in 1983 (voted the year’s “most expensive” bird by members); both Long-billed and Eurasian Curlews on Monomoy and another Ross’s Gull (seen just one day in Newburyport) in 1984; and many other state-record birds. One could go on and on listing the envy-inducing vagrants on the bulletin’s Checklist Summaries (not necessarily seen on BBC trips) for the “mind-boggling” year of 1979, with its “inexhaustible flow of rare discoveries,” or The Big Year of 1983.

With rarities came intensified efforts to find certain birds and, when targets or rarities were found, to get the word out quickly. A big step had been taken in the late 1960s with The Voice of Audubon-for years, the voice of Ruth Emery, known for her helpfulness and graciousness to all callers, whether expert or clueless, even the woman who indignantly insisted that the bird she’d just seen was a Passenger Pigeon. In 1982, still smarting over the Sharp-tailed Sandpiper that a BBC group had missed by two hours in 1973, the club supplemented the VOA with a Bird Alert Hot Line. A team led by Ida Giriunas and Herman Weissberg established a code for degree of rarity and fast-activating phone ladders, and the Hot Line helped many members see, among other birds, an Ivory Gull in Salisbury in 1983 (after 18 inches of snow) and, in Concord in 1986, a Fieldfare, the 4th record in the Lower 48. BBC directors, well-aware of the need for well-documented sightings, struggled with the question of how (and who) to verify rare bird reports. Another innovation, the club’s CB radio patrol, was illustrated in the 1985 report: “Come in, Barn Owl. We’re at the salt pans. The Tundra Swan just landed.” Bill Drummond, a dedicated patroller described by Jerry Soucy as a “super-active” target-finder, polled members to list their 10 Most Wanted Birds and then recommended strategies for finding the birds. Red Phalarope, Barn Owl, and Hawk Owl topped the list in 1979.

As the BBC grew larger and more complex, leaders engaged in regular self-examination. Overall, they believed, the club remained fundamentally sound. The BBC offered the “pleasures of group birding, the opening of doors on the world of nature with no strings attached.” The club was growing because newcomers were “not intimidated but welcomed.” Club trips, totaling 242 by 1980, were well-attended. Leaders, all volunteers, were helpful and knowledgeable, while representing a social cross-section: teachers, bakers, doctors, painters, ministers, mechanics, and accountants. Lectures drew audiences of up to 200 for talks ranging from Joy Viola’s 1972 “Bananaquits in the Lemonade, Motmots in the Bedroom” (on Trinidad and Tobago) to Peter Alden’s 1987 advice on “Finding Birds around the World.” Officers and directors managed club business effectively and, as president Alden observed in 1978, with a “minimum of antagonism.” They considered how to deal with “the few difficult participants” and suggested means of self- improvement on rare occasions when trip leaders were justifiably criticized.

But there were causes for concern, especially the dwindling role of young birders. From its founding the BBC had cultivated “junior” birders. In 1966 Mary Lou Barnett praised the “tenacity and bravado of our more youthful leaders.” In 1988 Larry Jodrey recalled when Dick Veit, Chris Leahy, Peter Alden, and Simon Perkins-all prominent figures in Massachusetts birding-were young club members, looking “quite innocent in those days, full of wonderment.” The BBC continued to offer novice-walks to teach ID skills and John Andrews’ birdsong workshops at Mt. Auburn, while individuals made it a point to recruit and mentor beginners. Yet by the 1970s, active young members were scarce in the club. Rick Heil recalls that when he led his first BBC trip as a teenager in 1975, he might have been apprehensive about making a wrong call-“I didn’t like making ANY mistakes!”-but because he’d been welcomed into the club by so many leaders, he wasn’t nervous about guiding participants generally old enough to be his grandparents. Yet, though Heil led club trips for the next decade and headed up the Newburyport CBC, he rarely met birders near his age.

Another ongoing concern was the necessity of good public relations. Club leaders encouraged members to adhere to ethical standards of birding, avoid trespassing, and maintain strong bonds with conservation groups (especially Mass Audubon), refuge managers, the Friends of Mt. Auburn (founded in 1986), and residents in popular birding areas. When complaints about inconsiderate birders threatened access to prime spots like Mt. Auburn and Plum Island, officers responded quickly, reminding members to observe birding etiquette and meeting with Parker River refuge managers to resolve problems (illegal parking, pressure for beach access) and formulate “development/rehabilitation plans,” while members joined in Johnny Horizon refuge clean-up days and the annual Eagle Survey. One 1983 meeting with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was cited in club minutes as “a fine example of grassroots democracy.” The BBC also worked frequently on joint projects with Bird Observer and other bird clubs like the Essex County Ornithological Club and the Forbush Bird Club’s annual photo contest.

Bird conservation was also a recurrent issue. In the 1920s Raymond Talbot had announced “his ambition to make the club an active force in conservation,” and over the years the BBC worked to make that ambition a reality. In the 1940s the efforts of Mass Audubon and the BBC helped establish the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge “to provide feeding, resting, and nesting habitat for migratory birds.” In 1963, after the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, the BBC joined the campaign to oppose indiscriminate use of pesticides. In 1968 the club formed a conservation committee, chaired by Joe Kenneally, who urged members to lobby to influence pending legislation such as a state Endangered Species bill, the establishment of a Non-game Wildlife Fund, and attempts to rescind the Wetlands Protection Act.

Locally, the BBC contributed funds for Least Tern research and protection projects on Plum Island and Crane Beach, Purple Martin houses in Ipswich (with the Trustees of Reservations), Barn Owl nest boxes on Martha’s Vineyard and the Boston Harbor islands, Osprey platforms at Belle Isle Marsh and Plum Island, and the Manomet Operation Recovery and bird-banding station. The club also strived to preserve habitat at such places as Dwyer Farm in Marshfield, Common Pasture land in Newburyport, and shorelines targeted for dredging projects. Members participated in a five-year Cardinal-Titmouse survey (in 1972, 4800 Northern Cardinals and 4200 Tufted Titmice were found in the state), annual Christmas Bird Counts, and the nation’s first statewide Breeding Bird Atlas, started by Mass Audubon in 1974. Paul Roberts headed up volunteers for the Eastern Mass Hawk Watch, with watches at Mt. Wachusett, Mt. Watatic, and Plum Island. A 1978 report described a group of BBC hawk-watchers as “arm- weary and bleary-eyed” at day’s end. Roberts also helped to organize the annual New England Hawk Watch Conference and, with David and Dennis Oliver, launched an American Kestrel nest box program. Nationally, the BBC supported conservation initiatives in San Francisco, the Everglades, and Alaska.

Despite these efforts, there was a gradual shift in emphasis from the overriding concentration on bird protection in the club’s first few decades. Since 1913, the first sentence of each blue book had announced that the BBC was “open to all who are interested in birds and their protection,” but in 1965 the phrase “birds and their protection” was changed to “birds and nature.” In 1977, after the Argo Merchant oil tanker disaster, a debate over the club’s conservation role was prompted when Soheil Zendeh and Craig Jackson wanted the BBC to circulate a petition to Secretary of the Interior Andrus to “stop the leasing of offshore tracts for drilling of oil in the North Atlantic-Georges Banks area.” Some club leaders believed that conservation required political activism. Others argued that the BBC “should stick to birding” and not ally with specific political causes. According to club minutes, directors in executive session allowed Zendeh and Jackson to circulate the petition at the annual meeting, but the consensus was that, out of fear of involvement with seemingly endless controversies, “we should not get involved with politics.” Directors resolved that the BBC would take no action on political controversies but that members could choose to be politically active as individuals.

As the club reflected on its purpose, members also looked back on BBC history. In 1964, Dorothy Caldwell was struck by “the slow death of the railroads” and “the weathering of the Bluebird crisis.” In 1972, Joe Northway reminisced about joining the club in 1928 to pass a Bird Study test (“the most difficult badge”) to become an Eagle Scout. He feared he wouldn’t be accepted by “society people” from Brookline but was warmly greeted by Raymond Talbot and Grace Snow, “thrilled by the friendliness of the group,” and found a dozen life birds at the Ipswich dunes. Ida Giriunas recalled a day in her garden when a Rose-breasted Grosbeak showed up: “I put down my gardening tools and haven’t picked them up since.” Larry Jodrey memorialized Clara de Windt, a BBC trip leader and “excellent birder” who was known for her “bright scarlet snow-bunny suit” (her “winter plumage’) and “would have made a figure descending the grand staircase at the Metropolitan Opera.” She exemplified the “you show me your birds, I’ll show you mine” spirit of BBC birding. Her marker at Oak Hill Cemetery was engraved with a chickadee. Jerry Soucy remembered certain endearing birds-a Yellow-headed Blackbird that put down at a Beverly wine-tasting gathering, and a Baltimore Oriole in Magnolia that, for over a week, flew indoors each night to sleep in the same shoebox-while marveling that Evening Grosbeaks were gone and that, “bizarre as it may seem,” Turkey Vultures were becoming “precursors of spring.” He wondered if the BBC had “lost a little something along the way” since the simpler days of birding earlier in the century. In 1975, stepping down from a “labor of love” as bulletin editor, Mary Lou Barnett said that nothing had enriched her life as much as birding and the BBC.

Looking back, the club also celebrated some of its stalwarts, granting merit awards or honorary life memberships to leaders who had enabled the BBC to thrive and enhanced the culture of birding in Massachusetts and beyond. Lillian Files, the leader of the American Bluebird Society, and Elizabeth Cushman, founder of the Student Conservation Association, were both granted special recognition. Ruth Emery received a tribute for her knowledge and dedication as a Bird Observer editor, Mass Audubon’s record compiler, and liaison between Mass Audubon and the BBC. Longtime bulletin editor and statistician Barnett; longtime corresponding secretary Natalie King; Virginia Albee, recording secretary for over two decades; and Dick and Dora Hale, who were club hosts, financial managers, and befrienders of new members, were all honored for keeping the BBC going strong. Larry Jodrey was thanked as a former club president, club historian, and ongoing source of wisdom. In 1975 he organized a surprise party at the Big Enuf cottage in Nantucket in honor of Jerry Soucy, who was commended for setting a “standard of excellence” as bulletin editor, author of the annual Checklist Summary, coordinator of roughly 3000 field trips, poet, philosopher, and teacher of countless birders.

Meanwhile, new members were responding to pleas for trip leaders and then emerging as leaders of the club. Bob Stymeist led his first BBC trip to Nahant in 1966 and went on to become compiler for the Greater Boston CBC and Breeding Bird Count, author of the Checklist Summary in 1984 (he was nervous about acting as “arbitrator” and living up to Soucy’s example), club president in 1985, and statistician from 1987 to the present, while finding time for a “lusty campaign” to add Rock Dove to the MAS checklist. Steve Grinley (first trip in 1965 to Mt. Auburn and Fresh Pond) led innumerable trips for the next four decades, became president in 1979, and was instrumental in maintaining good relations with the Parker River refuge. Herman d’Entremont (first trip in 1966 to Newburyport) carried on the tradition of Martha’s Vineyard trips and became the club’s program coordinator. Ida Giriunas (first trip in 1968 to Reading and Wakefield) organized the Hot Line, made Downeast Maine a regular club destination, became president in 1999, and continues to organize trips that make the BBC a leader in East Coast pelagic birding. Bill Drummond (first trip in 1972 to Newburyport) became bulletin editor and field trip coordinator in 1977, then president in 1987, reached out to novice birders, and pioneered BBC trips across the country. When he stepped down as bulletin editor, his successor, Doug Resnick, praised his “monumental” contribution to the BBC, “his commitment to collegial birding combined with creativity and precise attention to detail,” while Drummond acknowledged a debt to forerunners like Stella Garrett and the Hales, who exemplified the club’s “spirit of sharing.” Paul Roberts (first trip in 1976 to Great Meadows) became the dean of Massachusetts hawkwatching and then club president in 1983. David Oliver (first trip co-led with brother Dennis in 1979 to Plum Island) took over the demanding role of bulletin editor/field trip coordinator in 1986. Many others, like club presidents Leslie Vaughan, Warren Harrington, Herbert Murphy, Richard Holman, Lawrence Cyr, Tom Tomfohrde, Eliot Taylor, Joe Kenneally, Peter Alden, and Alden Clayton, played invaluable roles in guiding the BBC.

In 1987, her last year as statistician, Barnett thanked all the trip leaders who had “made neat, concise, scientific remarks” or decorated their field cards with “exuberance and poetry” or were so prepared that “every bird is tied down and ready to sing on cue.” Bill Drummond also praised trip leaders for their dedication, innovations, determination to maintain club traditions, and expansion of club birding throughout and beyond Massachusetts. Among these leaders were Jim Berry, a steady patroller of Crane Beach and now one of the reigning authorities on the birds of Essex County; BBC director John Nove, who specialized in “on foot” trips and led an annual Ipswich River canoe trip sponsored by the Essex County Ornithological Club; Ann Blaisdell, who revived the traditional New Year’s Day walk, now in Newburyport; Bob Stymeist, who, in addition to Mt. Auburn walks, guided nighthawk watches and a 70th anniversary excursion to Thompson Island; Lee Jameson, Steve Grinley, and Paul and Julie Roberts, who led Berkshires campouts; Mark Lynch and Sheila Carroll, who extended coverage in central and western Massachusetts, including a “Feast or Famine” search in Savoy and Windsor and an “ingenious” birders’ tour of the Worcester Art Museum; Jim Barton, who led regular, strenuous trips to Monomoy Island; Dorothy Davis, a leader of Nantucket trips; Sherm and Sue Denison, Carl Turin, Stuart Henderson, Father Ray Prybis, and Ida Giriunas, who took members climbing in the White Mountains and on excursions to the Connecticut Lakes, Machias Seal Island (a “birder’s paradise” in Ida’s words), and “Spruce Grouse Lane” in Maine; and Drummond himself, an inveterate trip leader who tried out a “Texas style birding” walk with a midday break in July. In addition to Ida Giriunas, Herman d’Entremont, his nephew Glenn d’Entremont (later a club president), Chris Corley, and Martha Vaughan all led and/or organized regular trips that made the BBC the cutting edge in New England pelagic birding.

Further afield, club trips included a Stymeist-led “Southern Sweep” from New Jersey to North Carolina, weekends at the Maryland shores led by Charles Vaughan, pelagic trips off the Outer Banks, and a boat trip in the Dry Tortugas. In the early 80s, Bill and Barbara Drummond told stories in the bulletin of their adventures in the Colorado Rockies (a “birding honeymoon”), Alaska, Arizona by way of Alabama, and Peru. A few years later, Bill Drummond began leading annual club trips to prime birding locations around the country. From his travels he concluded that no other birding club he’d found had “anything like what we have.”

The BBC continued to find great birds in the late 1970s and 1980s. 1979 featured “the winter of the owl,” with at least 18 Great Gray Owls in the state, along with ten Short-eared and four Long-eared Owls at Salisbury and Plum Island. Golden-winged, Blue-winged, Brewster’s, and Lawrence’s Warblers were all seen on one day in West Newbury. In 1983 a White-faced Storm-petrel was found on a BBC/Bird Observer trip to Hydrographer’s Canyon, and “sea trips became the year’s sensation.” Bob Stymeist’s 1986 Checklist Summary was titled “The Tropicbird and 360 Others.” A Red-billed Tropicbird at Gay Head and the Fieldfare in Concord were both state records. 1987 brought what Stymeist called “the thunder from Down Under,” a rare Australian Cox’s Sandpiper (eventually determined to be a hybrid) that drew thousands of birders to Duxbury. In 1988, club members were torn between a warbler and a state-record pipit for their bird of the year. Stymeist’s Checklist Summary headline read “The 1988 Election: Sprague Tops Swainson.” In the 1980s club trips regularly found over 300 species in the state each year (314 in 1984), and the BBC life list was inching toward 400.

For club members the most memorable birds were often rare, sometimes not: an Ivory Gull that “floated by on an ice flow” with “Cleopatra-like” dignity; the “terrible beauty” and drama of a Snowy Owl that captured a Ring-necked Pheasant one New Year’s Day on the South Shore; a Gray Catbird imitating a Gadwall on Plum Island; a Chuck-will’s-widow floundering over Stellwagen Bank; a Cerulean Warbler landing on a boat headed for Hydrographer’s Canyon; a Burrowing Owl that “lived under a plastic bag” on Martha’s Vineyard; an escaped Chilean Flamingo found on Monomoy; a Gyrfalcon chasing two Red-tails across the Quabbin; a rare Sutton’s Warbler subspecies that generated “spirited discussion” at Mt. Auburn; and a “crazy gull” cited by Stymeist as Kamikaze Bird of the Year for sitting on the head of a Humpback Whale and trying to extract a fish from its mouth. Some days were remarkable for the sheer number of birds: 20 warbler species bathing in a brook at Nahant Thicket in 1982, a “fantastic fallout” of 21 warbler species in one hour at Plum Island in May 1987, and, that same year, 20 South Polar Skuas at Georges Bank.

The Checklist Summaries for these years also noted changes in bird distribution. By 1975 Harlequin Ducks had become regular in Rafe’s Chasm in Magnolia. In 1979 Wilson’s Phalaropes first nested in the state at Plum Island, but “thrushes were alarmingly down.” Bald Eagles returned to the Merrimack River in 1980 for the first time in years, and the next year was notable for “the diversity and number of Bald Eagle reports statewide,” but Roseate Terns and Golden-winged Warblers were declining. Missing from BBC lists in one or more years between 1975 and 1988 were Razorbill, Greater Shearwater, Redhead, Eastern Bluebird, and (in many years) Connecticut and Worm-eating Warblers. Some members were distressed by personal misses, like the “phantom” Gyrfalcon that teased numerous birders. Several lamented missing Whip-poor-will in consecutive years. 1981, judged by some members as one of the best years ever, was also one of the worst for some who’d missed various rarities.

Beyond personal misses, trip reports remind us that birding is a take-your-chances proposition. In 1981, Mimi Murphy observed about a Needham trip: “When a red squirrel is the first animal in half a mile and the group starts to collect mushrooms, you know you’re in trouble.” (The group finally found one junco.) In 1983, Jim Berry described a February Ipswich trip with “brutal, bone-chilling” NE winds: “When you don’t even see a Red-breasted Merganser, you know you’re in trouble.” (Participants sought shelter in the dunes.) Berry’s Ipswich trip the next February, with treacherous driving and one participant, continued the theme: “When a Brown Creeper is the highlight of your walk . . . ” But virtue has its rewards: that June in Ipswich Berry led “one of the finest evening trips in years.” While watching a Forster’s Tern and Caspian Tern at Crane Beach, he recalled his father’s expression: “Every blind pig finds an acorn once in a while.”

Sometimes good karma rewarded the club’s friendliness. One day, members were welcomed to view a Harris Sparrow, Varied Thrush, and Oregon Junco on the Winthrop Estate in Ipswich just before the French ambassador showed up for lunch. In Boxford, a woman invited members into her house to view a Carolina Wren, then headed out on an errand and asked them to lock up after themselves. Hopefully they were less absent-minded than the birders routinely reminded in bulletins not to lock themselves out of their cars, or the bird-distracted driver in a Plum Island caravan who rammed Paul Roberts’ car, twice, on one of Roberts’ first club trips.

BBC lore from this period focuses on the birders as much as the birds. In 1984 Jerry Soucy teased his friend Larry Jodrey about seeing a Eurasian Curlew on Martha’s Vineyard and finally justifying his CURLEW license plate. In Maine, a BBC group tromped into the woods in search of Spruce Grouse, while their intrepid leader, Ida Giriunas, on crutches, stayed back and found several Black-backed Woodpeckers. Jim Berry recalls the day he recruited Ida to join him for the Cape Ann CBC on a “VERY cold and windy” day at Crane Beach. Afterwards, she informed him that she was “never going to do that death march again!” Bill Drummond inspired countless stories. Charlie Campbell’s “Real Diary of a Non-Birder’s Weekend Trip to Martha’s Vineyard” in a 1979 bulletin describes the leader as a “nice young man” from Haverhill who “organized everything extremely well” and “must have served some time in the service of Her Majesty, as he swung his arms marching in a British military manner while leading us through woods, swamps, rocky shores at the foot of cliffs and over sand dunes.” In “A Birder’s Paradise,” Michael Corkery, a 7th grade Latin student of Barbara Drummond, tells how impressed he was to find a car (a Volkswagen Jetta) with a CB code name (Red Crossbill) when Barbara and Bill took him to Mt. Auburn and “initiated [him] into the honorable life of birding.” Many members recall being urged by Bill to “get on that bird if it’s the last thing you ever do.”

When club members look back upon their early days in the BBC during the 1960s and 1970s, they talk about the gracious welcome they received from the club regulars, the fun they had on club trips, and the opportunities they were given to find new birds, new birding locations, new bird behavior, and new birding companions. They never fail to mention those who reached out to become their mentors and friends, people like Larry Jodrey, Gerry Soucy, Evelyn Pyburn, Herman Weissberg, Phil Parsons, Natalie King, Dick and Dora Hale, Lawrence Cyr, Alden and Nancy Clayton, Bill and Barbara Drummond, and Herman d’Entremont. Jane Lothian recalls how Dick and Dora Hale would welcome “bedraggled birders” on Cape Ann into their Rockport home to eat their bag lunches out of the wind. When the Hales asked her to sign a guest book filled with comments from past BBC trips, she felt she’d become part of a club tradition-a tradition of hospitality that continued for years even after it became difficult for the Hales to join trips themselves. Rick Heil particularly appreciated the enthusiasm of Stella Garrett, who would offer him a little gas money if, “with my young eyes,” he could find her a Kentucky or a Connecticut warbler. Paul Roberts recalls the trip when Herman d’Entremont finally identified the “incredible song”-a Winter Wren’s-that had tantalized Paul and his wife Julie on pre- birding-days hikes up Mt. Monadnock. Steve Grinley fondly remembers the camaraderie of Greylock campouts, when BBC groups would gather around campfires, cook their own dinner, share wine and stories to a chorus of thrushes, and relive the excitement of finding Bicknell’s Thrushes nesting on the summit at Bascom Lodge. Some longtime members worry that, while it may now be easier to target birds and share information in the era of the Internet and digital birding, the club, and birders generally, may be losing some of the companionship, the personal communication, and the spirit of sharing that have always marked the BBC. Yet these same members share a sense of pride in the club’s contributions to ornithology and bird conservation, and they all express gratitude for the many ways in which the club has elevated their lives and introduced the delights of birding to thousands of others.

In 1988, club president Bill Drummond presided over a BBC 75th anniversary celebration at Bentley College, attended by over 350 members and guests. Victor Emanuel, a pioneer in guiding international birding tours, was the featured speaker. In his address to the club, Larry Jodrey recalled his first encounter with the BBC at Andrew’s Point in Rockport in the early 1950’s. A “horde” in all sorts of winter plumage descended upon him and handed him a blue booklet. The dollar he paid to join the club was “the best investment I ever made.” Jodrey reminded members of their debt to their forebears and their obligation to carry on the heritage of conservation and the encouragement of youth. “Generations go swiftly,” he said. “Others will take our place. We only share our heritage; we share the earth, for a brief bit.”